Video killed the radio star, said the Buggles (still debatable), but the conventional wisdom that MP3s killed vinyl just doesn’t hold true—at least, according to United Record Pressing of Nashville, Tenn.

In business since 1949, the company (originally called Southern Plastics) has been melting pellets of vinyl and pressing them into 7-, 10- and 12-inch phonograph records since 1962. Far from an anachronism in this age of digital music, United is expanding. In fact, management credits new technology with contributing to a rebirth of appreciation in vinyl. “Digital is the peak of convenience, and vinyl is the peak of experience,” explains Jay Millar, director of marketing.

The two formats can indeed work in tandem. According to Millar, about 75 percent of the vinyl records pressed (new albums, not reissues) come with a code for a free digital download of the same music.

“It’s very smart and consistent with the trend,” says chairman/CEO Mark Michaels. “You have the digital download on your computer or on your phone, so if you go jogging or you’re on an airplane you can listen to it, plus you get this thing that’s permanent. People want something permanent because music has meaning.”

A former consultant with McKinsey & Company, Michaels took the helm at United in 2007. While not releasing revenue figures, he says the company has grown from 40 to 150 employees since he came onboard. Approximately 70 to 80 jobs will be created when United opens a second Nashville plant later this year, an investment Mayor Karl Dean cited as an essential component to the continued strength of Music City.

United’s resurgence was helped by labels with major indie cred, like rocker-producer Jack White’s Nashville-based Third Man Records, which began working with the pressing plant in 2009. Now jazz, hip-hop, electronic and classical records are all being released on vinyl.

“If you go through the Billboard charts, you’ll be hard-pressed to find a title that’s not coming out on vinyl,”

Millar points out.

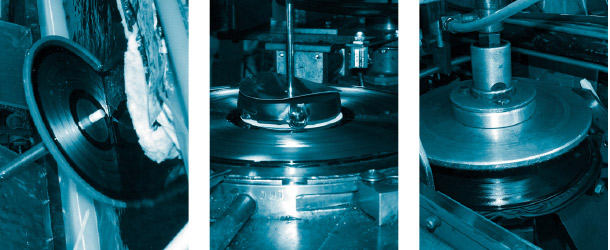

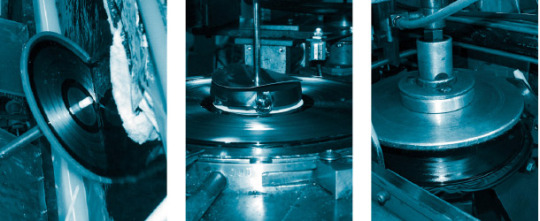

United’s presses run 24 hours a day, six days a week, making about 40,000 records each day. That capacity will double by the end of 2015, when the new plant is fully operational. In addition, delivery times will be reduced from

three or more months to closer to one month. Since record presses are no longer being manufactured, United buys its

machines from companies that are going out of business; there is one machinist on staff who specializes in repairing existing equipment.

Order sizes for vinyl are smaller than those for a CD printing: typically 1,000 to 5,000, but they can run anywhere from 300 to 50,000. Unlike with CDs, retailers are not typically allowed to return vinyl records to record companies, so the labels are more likely to place small repeat orders than one large one.

“People at the store level tend to order a bit more conservatively, and thus the labels order a bit more conservatively, because they don’t want to sit on a lot of it,” Millar explains.

He estimates that United’s product represents 30 to 40 percent of all new vinyl on retail shelves at locations ranging from independent record stores to Amazon to nonmusic retailers such as Whole Foods Market and Urban Outfitters.

About 60 to 75 percent of United’s pressing business is new releases; the rest consists of reissues like the Pretty in Pink soundtrack, which was pressed on pink vinyl. The company also handles distribution and records a series, “Upstairs at United,” on its own 453 Music label, with bands including JEFF the Brotherhood. These all-analog recordings capture the ambient noise of the record presses in operation.

Millar is confident that United will continue to evolve alongside the music industry. “As long as there is great music,” he says, “there will be people eager to get it into people’s hands and their ears.”