When similar companies compete primarily on price, it’s a race to the bottom. Strategy and innovation consultants Jeffrey Phillips and Alex Verjovsky say no one, least of all the customer, wins when eroding margins reduce levels of quality, differentiation, and service from businesses competing with so-called “attrition strategy.”

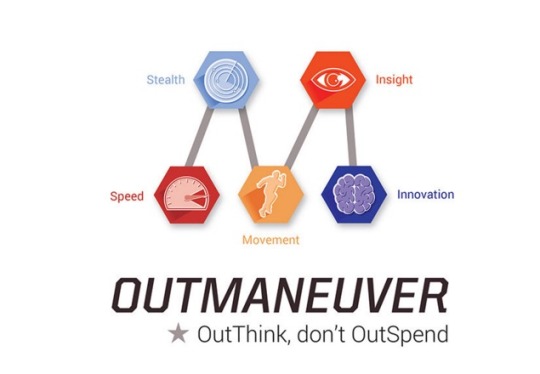

They suggest a better way, which they describe in their new book Outmaneuver: OutThink, Don’t OutSpend. Called “maneuver strategy,” the authors say it’s been used by the military since King Leonidas and Genghis Khan but is overlooked in business.

Aabaco Small Business had the chance to ask Phillips, who also pens the Innovate on Purpose blog, a few questions about maneuver strategy and the new book.

Aabaco Small Business: Can you explain in a nutshell what sets Maneuver Strategy (as well as preemptive, disruptive, and dislocation strategy) apart from any traditional competitive approach to business?

Jeffrey Phillips: Traditional strategy seeks to match the leading products feature for feature. If a company enters a market, the most typical entry is to understand what the market leader offers, create products or solutions that carefully replicate what the leader offers, and then create some differentiation, usually around cost or service. This means that, for the most part, most competitors in an industry offer relatively undifferentiated products that compete head-to-head, leaving only promotion or price as differentiators. This creates a race to the bottom, driving prices lower.

Maneuver strategy does not seek to match a competitor’s offering or strategy. Instead, it examines a market and looks for three opportunities:

- Can we preempt the existing competitors by entering a valuable but unoccupied segment, niche, or market. Rather than compete head-to-head, can we carve out a market space with little or no competition? This is what Southwest did when it entered the market against TWA, Pan Am, and others. It targeted people who might have used a bus or a car. The major airlines simply weren’t targeting these customers.

- Can we dislocate the existing competitor? Rather than compete against the entire offering, are there significant gaps or weaknesses that, if attacked, will cause the competitors to lose share and compete with less than their full strength? In the book we used Zara as an example. Zara noted that the fashion houses have decided on a convention: a few model changes or updates each year on a specific cycle. Zara decided to ignore that tacit agreement and speed up the delivery of new fashions. The existing fashion houses could not keep up and lost market share.

- Can we disrupt our competitors? Sometimes there is no easily available unoccupied space, and competitors don’t have glaring weaknesses. What a new entrant can do in this case is to conduct activities or operations that cause their competitors to rethink their plans, or implement plans in a less effective way. We call this “throwing grit in the gears.” In the book we point to a small Guatemalan chicken restaurant that competes with KFC. They used psychological disruption, noting that all their food was grown in Guatemala, and calling on their customers to support the Guatemalan chain. Amazon uses this technique effectively, constantly putting out press releases about potential new products, which disrupt its partners and competitors plans.

Ultimately, maneuver is focused on avoiding head-to-head competition, always seeking to win the most market share or profits at the least possible cost, leveraging speed, insight, agility, and innovation over brute size or strength

ASB: Is Maneuver Strategy a fit for all kinds of small businesses and long-established businesses? If so, what, if anything, is different about how small businesses should apply it?

JP: Small businesses and entrepreneurs actually have an advantage when using maneuver, because they tend to be a bit more agile and often make decisions and implement them more quickly than larger businesses. Both large and small businesses can benefit from maneuver, but larger businesses often have to change their business models or corporate cultures somewhat to introduce more speed, agility, and innovation while these are often natural capabilities that small businesses regularly practice. The tools and techniques are the same for companies of either size.

ASB: You say speed and agility have become more important than size and strength. Can small businesses use maneuver strategy to compete head-to-head with big businesses?

JP: Absolutely. A good military example in the book refers to Fort Eben Emael. At the start of the Second World War it was considered the most powerful fort in the west, and almost impossible to attack. The Germans knew they had to conquer that fort before they could attack France. It was assumed that it would take tens of thousands of soldiers weeks to attack and defeat that fort, yet using speed, agility, and innovation, the Germans defeated the fort in less than 90 minutes with less than 100 men.

How? They attacked from the top, landing gliders on the roof, which the fort’s defenders never anticipated. They fought very quickly and won before all the fort’s soldiers, some of whom didn’t live in the fort, could rally and fight back.

This is an example of a very small force beating a much larger group. In the same way small firms can use maneuver to compete with big businesses, because big businesses tend to have more inertia and less innovation and agility than smaller firms.

ASB: What skills does a person need to run a company according to this strategy?

JP: From a small business perspective, implementing maneuver is about building an organization that retains its ability to make quick decisions, to delegate decision making to trusted team members, to move and adapt quickly to changing market environments, and to constantly innovate.

Another key factor is the ability to gather and process a lot of market and competitive information and trends, so that your management team has better insight about what’s happening and what’s going to happen. This translates to leaders who promote insight and market intelligence, who encourage innovation, who ask their teams to reconfigure themselves to meet the changing market, and who can use insight to find unoccupied spaces or critical competitor weaknesses.

ASB: Could a manager within a company that does not follow this philosophy run their own department using your strategy?

JP: Yes, the book is written to address three levels of management: a product manager, a line or department manager, or a CEO. These ideas and methods can be implemented at a product level or a line of business level.

ASB: I know you offer case examples from Zara, Airbnb and some other large organizations. Can you provide any small business anecdotes?

JP: Tesla, Airbnb, Uber, and others are now larger firms but were all once simply entrepreneurs. They all used most of these techniques to grow to what they are today. We can identify other very small firms using these tactics but they might not have a lot of publicity, and may not want it.

ASB: What about the idea of seeking win-win outcomes in business?! Is business really as cut throat as war so that military strategy applies?

JP: We’d need to separate the concept of partners and customers from competitors. There are definitely win-win opportunities with partners who augment or complement a product or service, and win-win opportunities with customers. When we talk about competitors, however, that’s bare knuckle competition for the most part. There’s a reason the Blue Ocean people describe most competitive scenarios as bloody red oceans. If you look at most industries, you’ll see a handful of competitors slugging it out for market share and profits. Their competition is very much akin to warfare, and they have adopted much of their strategy and language from the military – look at books like “Marketing Warfare” for instance.

There is an emerging class of more social or triple-bottom-line businesses that may not be as competitive, but the vast majority of firms operate in highly competitive markets. Schumpeter didn’t describe capitalism and innovation as “creative destruction” without cause.

- Type article

- Author Adrienne Burke

- Image https://68.media.tumblr.com/143a7abdb47167abbc29deb3c3fbf7e1/tumblr_inline_o6ru5odQ2o1si4p7w_540.jpg

- Provider Yahoo Small Business Advisor