The Stingray is a device that can track cell phones in real time. It is a type of IMSI catcher. IMSI, the International Mobile Subscriber Identity, is built into all cellular phones. The IMSI number is broadcast by a phone when it connects to any cellular tower. An IMSI catcher pretends to be a cellphone tower, “catches” the IMSI broadcast, and then can act as a relay to a legitimate cellular phone tower, meaning that everything that is broadcast across the IMSI catcher can be heard or intercepted.

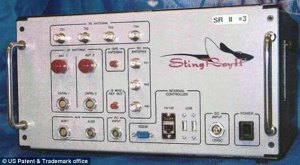

The Stingray IMSI Catcher

There are many IMSI catcher devices on the market. Some of them are “active” intercepts and others operate passively. Stingray is the product used by the FBI and law enforcement. Its capabilities are kept secret from the public.

All cellular phones encrypt the connection between the phone and the cellular tower. Thus for an IMSI catcher to be any good, it has to break the encryption or defeat it one way or another.

Essentially there are two ways of getting rid of the encryption: Knowing the algorithms used by the phone companies and how the key is composed or finding a means to turn off the encryption. Both are feasible strategies and it is likely that Stingray employs both strategies and perhaps others.

The IMSI catcher is a tool for law enforcement, for intelligence agencies, and for criminals. Other than Stingray, many of these devices can be bought online. And the US government also supplies such devices to friendly foreign countries and foreign entities.

The heart of the FBI case is that it can use the Stingray because the public has “no reasonable expectation of privacy” when using a mobile phone. This argument is not generally accepted, and nine states, including Virginia and Maryland, require a law enforcement agency to get a warrant if the agency wants to use a Stingray device, or to agree in advance on the protection of information gleaned from cellular phones that are not part of a current law enforcement investigation.

The expectation of privacy issue was first brought out in Smith vs. Maryland (1979). In that case law enforcement used a “pen register” to record the time, duration and phone numbers called from a phone line belonging to a suspect. The Supreme Court said that the pen register (an electro-mechanical device) did not record actual phone calls and that use of a pen register did not rise to a violation of either the First or the Fourth Amendments (e.g., Freedom of Speech, Illegal Searches and Seizures). In an earlier case, Katz vs. U.S., the Court held that warrantless wiretaps were unconstitutional searches and seizures because the public had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Katz was decided in 1967, before the cellular phone era.

The FBI is not relying entirely on its argument that the public has no reasonable expectation of privacy when using a cellular phone. It also argues there are urgent circumstances, such as preventing the commission of a crime or stopping a terrorist, where a warrantless wiretap of a cell phone is justified. To my mind, law enforcement has to have the ability to make an informed judgment there is an imminent risk, and law enforcement should be able to move against these threats. The same idea is what was behind the War Powers Act, which recognized that the President as Commander in Chief needed flexibility to protect American national security. Law enforcement needs the same flexibility.

The question is whether one should hang that argument on the idea that the public lacks a reasonable expectation of privacy when using mobile devices. It seems to me the stronger case is the ability to respond to a concrete threat.

And therein lies the rub, to quote the Bard. Law enforcement has to take a risk when it uses the argument of dire necessity to justify acting without a warrant. In other words, law enforcement will need to defend those decisions before an impartial court if challenged. Law enforcement cannot, willy-nilly run around setting up fake cell towers just to suck up as much information as it can. Right now, except in those states where there are laws on the books, the standards for law enforcement operations when it applies to IMSI catchers, are far from settled. That is why, short of specific legislation, the use of Stingrays may end up in the Supreme Court.

This article was syndicated from Business 2 Community: Will The Stringray End Up At the Supreme Court?

More Technology & Innovation articles from Business 2 Community:

- 15 Business Stats For Starting 2015 Off Strong

- Japanese Police Believe Missing Mt Gox Bitcoins Likely An Inside Job

- Google’s Project Zero Exposes Windows 8.1 Bug Before Microsoft Can Patch It

- Software Sprinting: What Is Rapid Application Development?

- IC Real Tech Lets You Stream Virtual reality With 720-Degree Allie Camera